I took my girls camping in Colorado back in July, still impervious to the emerging patterns of my life. Under this life’s new rules, all my races in the year 2024 are undone before they start—most often in surprise attacks by an odd menagerie of wild creatures.

My inaugural Louisville Classic was nearly undone by a family of squirrels.

And before this year’s Solstice 100, I was crossed by a grey wolf, then flattened by a mosquito.

So I should have been on high alert camping in the Rockies, a week or so out from my first Day Across Minnesota (DAMn). But I wasn’t. Beth and I had escorted our daughters to Golden Gate Canyon State Park for an “altitude camp out” with the Lincoln High girls’ cross country team. And I can’t say we weren’t warned.

We met an older woman from Missouri in the first meters of our first day’s first hike. I can’t remember her name—Connie? Cassie? Cassandra?—but I remember what she said.

“Watch out. There’s moose on this trail.”

This friendly woman went on at length about the animal’s underappreciated fury, and how the last thing you want to be in this life is on a moose’s bad side. She even gave us tips for telling whether we were too close.

“Hold your thumb out square like this,” she said. “And if your thumb don’t block out its inn-tire head, hardware and all, friends, you are too close. And y’all need to back y’allselves up.”

As an elder in our group, I thought it important to model listening to one’s elders. So I did. Patiently. But inside, I was dismissive as heck.

“Oh, sweet grandma,” I told myself. “Would you look at us? We’re a dozen high school girls and six stumbling parents. There won’t be a mammal this side of the mountainside that doesn’t know we’re here 20 minutes before we do. We won’t be seeing any moose on this hike.”

And we didn’t. Which made me feel pretty smart about the predictability of wild animals.

Then came less predictable events.

Our first moose arrived at our campsite during lunch. A juvenile male with a busted left antler hanging straight down. We snapped to attention as he grazed in the swampy meadow just downslope from our tents.

When he didn’t immediately see us and plod off into the woods, the girls held their thumbs out square and gauged: He was plenty close, but not too close.

He apparently preferred shade, and our campsite was protected then by a thick barrier of sunshine. Which felt like sunny news. The girls named him Ernie as he munched. And it fit. He was totally an Ernie. Through and through. Predictably.

Once his novelty wore, we decided to encourage Ernie to scram. We hollered. We beat a pot and a pan. The team’s saltier girls went so far as to antler shame. The captains allowed this as, technically, Ernie didn’t speak English, meaning mean words would never hurt him. One parent sidled over to our cars and laid on the horn.

Ernie didn’t care about any of that noise. He left when he was good and ready.

He would appear again and again over the next three days, always in this meadow he favored. And he became our camp mascot. (What’s up, Ernie? You good?) We recalibrated downward our sense of the risk he posed. And that worked fine until our last day on the mountain.

Whenever the girls went on their runs along the road above our campsite, my job was to bike along behind. I’d ferry them water bottles and tote whatever jackets they shed along the way.

A few of them wanted one last run before the long drive home. So I got the bike ready and put on my cycling shoes. I dialed them tight just as a new bull moose stepped out of the woods. He wasn’t monstrously large as far as bull moose go. But he was a good deal bigger than Ernie, with two antlers, wider, and both of them pointed in the direction God intended.

He was close to me, and I didn’t like it. A few yards beyond him stepped a cow and calf pair—the three of them a nuclear family ticking.

Every one of us knew this situation was new. And the old Ernie Rules did not apply. Most of the girls fled quietly to my right. Beyond our tents stood the cabin with its deck and railing. And they fenced themselves there.

One mom and a couple girls were closer to the vehicles than the cabin. They wisely shut themselves inside her SUV.

For some reason, I didn’t do either of those things. I told myself I couldn’t run in my cycling shoes. Which wasn’t exactly true. I couldn’t run well in cycling shoes. But the immediate circumstances didn’t yet call for running well.

I told myself the situation wasn’t dire, but I should probably move along to my closest safe space: the car parked next to Ashley’s SUV. But that meant moving toward the moose family. I’d need to do that delicately in Cinderella slippers.

The bull was closest, but he worried me least. I watched the (adorable) calf, figuring whatever that sweetie did next would dial the mother’s aggression up or down. I think I’d halved my distance to the car when the calf took an innocent step toward me.

That was not what I wanted that cutie to do. I told the calf “No,” in the calmest yet non-negotiable dad voice I could muster. I said, “No.” As in, “Young lady, you take your fork out of that toaster this instant.”

At my voice, the mother turned her head, looked at me with a skull far larger than my outstretched thumb, and charged.

I broke for the car.

The bull, caught between me and the cow, turned and fled his wife, inadvertently charging me as well. I reached Heidi’s car and thanked the Lord almighty she’d left the door unlocked. I slid into the driver’s seat—never mind the steering wheel in my chest—and pulled the door shut. The bull passed her side mirror, close enough to touch. The cow had abandoned her charge and returned to her calf in front of the parked car. And the bull pulled up behind us.

Now, everyone was safe. But we were locked down while the moose cooled their jets. There was no grazing in the trees behind us, so I figured the bull would come back downslope to the meadow with the cow and calf.

He did this on his own schedule, walking near me again as he grazed. At our closest point, he lifted his head and we looked at each other through the glass. A zoo in reverse gear—with wildlife passing my enclosure.

I could see individual flies bobbing at his eyes. Gold gnats walking the bridge of his nose. The window between us left no room to reach out my thumb to test—and that gauge of distance thumbed itself into a gesture of animal closeness: The gentle wiping clean of a Labrador’s eye.

I blinked this picture clear.

***

Nothing about this dust-up with a moose explains my failure to finish DAMn a few days later. But that tense encounter—and the three nights of sleeping on the ground that preceded it—set off a string of stresses that cost me too much sleep to handle a 240-mile gravel race with a midnight start. (I won’t bore you with everything I lost sleep over. But it was a lot. And I started that race already groggy.)

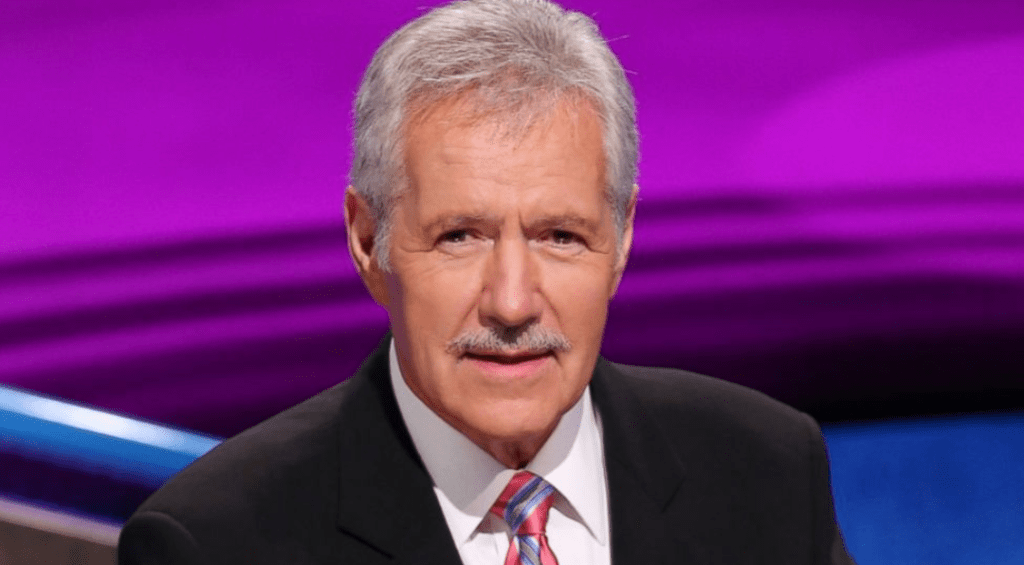

At one point before dawn, I caught my bike drifting right and snapped it back in line. I asked myself: Wide eye slide thataway? And the honest answer was because Alex Trebek had just stepped out of the fog separating wakefulness and sleep; he’d shoved me onto the set of “Jeopardy!” And I didn’t know a single bit of trivia.

Later, along a downhill swerve in daylight, I was introduced to speak on ankle fractures to a conference room full of clapping orthopedists.

I wasn’t ready to be here. My son picked me up at mile 170 and claims I took a nap I do not remember.

***

I think what happened with those moose applies more to the beastly heat we just saw at Gravel Worlds than it did to anything from my sleepless Day Across (most of) Minnesota.

For the first time in, I don’t know, eight years? I did not ride GW. I’ve already described my misgivings about how they communicated their leadership transition, and I don’t feel the need to belabor any of that. But I just couldn’t bring myself to sign up this time.

Even if I had registered, I’m afraid the wild forecast would’ve rendered me a DNS anyway. Anymore, riding my bike into 95-degree heat and 67% relative humidity feels about as safe as throat punching a grizzly.

It’s easy to see southeastern Nebraska as a place stripped of its wilderness. Author Kim Stanley Robinson wasn’t wrong when he called the Midwest something closer to “a continent-sized factory floor for assembling grocery store commodities.”

That industrialized aspect makes Nebraska appear to be a controlled environment. We’ve drawn it full of fence lines and row crops, crosshatched by the compass arcs of center pivots. And it’s easy to think our relationship with heat will stay inside those neat limits. That it will respect our boundaries like a Holstein respects wire.

But heat respects our fences about as much as sparrows do. And heat respects us the same amount. By the time we recognize we’ve ridden our bikes into summer’s wilderness—that not just our toughness is in play, but our kidneys and livers, too—we’ve already crossed a crucial line.

Once we enter that dizzy state, rider, we need to understand: We’re in moose-petting territory now. From here, we’ll either be close enough to reach safety—in the form of ice or air conditioning—or we won’t. And if we don’t reach cooler temperatures, the consequences run on the same rough spectrum as an animal stomping. Maybe you come away with a headache and an ambulance ride. Or maybe you don’t come away at all.

I believe heat now rivals vehicle collision as the largest danger gravel racers face. And I want to write soon about how riders and race directors can think about heat in the summers to come. This’ll be less storytelling and more information sharing.

Each one of us will continue to make our own decisions about what constitutes “safe enough” when we ride. Our risks vary based on a mess of factors all in play at once. And there is no simple thumb test. But I hope what I have to say might help you stay safe on your bike.